They call themselves “The Babymakers.”

Abrie Sellers and Sarah Brown of Thomasville CrossFit in Thomasville, Georgia, are among thousands of athletes who completed the first four workouts of the 2017 CrossFit Team Series this weekend. But their team is unique: at the start of Week 1, Brown, 38, was just 13 weeks postpartum after delivering a healthy baby girl, Zoey. Sellers, 33, had just hit the 25-week mark of her own pregnancy.

“With our mama forces combined, we make one badass female team!” reads the duo’s bio. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

“This is about crushing the people next to you, and this is about trying to win the fucking CrossFit Games,” Dave Castro, Director of the CrossFit Games, said at the dinner that kicked off the 2016 Individual competition. “If you’re not coming for that reason, you should just quit now.”

Tia-Clair Toomey, who took second in 2015, listened quietly.

“Personally, I never wanted to come to the CrossFit Games to win it. I just wanted to be there, you know?” she said during a Skype call two weeks before the 2017 Pacific Regional.

By the time the week was over and she’d taken second again—losing the title Fittest Woman on Earth to defending champion Katrin Davidsdottir by just 11 points—she’d come around to Castro’s way of thinking. As she drove down the StubHub Center’s palm-lined boulevard for the last time on Sunday night, she turned to Shane Orr, her fiancé and coach.

“What do I need to work on?” she asked him. “Because I want to win the CrossFit Games next year.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

Last Thursday, after Open Workout 17.5 was announced, Dave DeGroot had one thought: “Oh boy.”

The couplet of thrusters and double-unders called for 350 reps on the rope, more than the 47-year-old had ever done in a single workout.

Had it been a normal challenge programmed at his gym, CrossFit 808 in Honolulu, Hawaii, he would have scaled.

“But nope, it’s the Open,” he thought to himself. “I have a goal: Rx everything.”

A day later, DeGroot finished the final double-under of 17.5 at 37:26, last in his heat. Though disappointed at first, he looked at the big picture once he caught his breath.

“A couple years ago, I couldn't do double-unders, and 95-lb. thrusters would leave me gasping,” he said. “It’s good to keep that perspective.”

For DeGroot, a CrossFit Games Open competitor since 2012, that perspective spans six years and 30 Open workouts. Each year of tests, he said, has provided an opportunity to grow.

“The Open is a fun annual challenge—it's a way to benchmark myself against my age-group peers across the CrossFit community,” he said. “It's fun to be able to do that and see how I'm doing better.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

It’s 2:45 on a Friday afternoon at Lawrence High School in Massachusetts. Most students are surreptitiously packing their bags in the final moments of class, itching to escape to the weekend. But Eduardo Collado Rosario and Jeffrey Almanzar are not most students. Their Friday night plans include deadlifts, wall-ball shots, rowing and handstand push-ups.

Instead of bee-lining for the door after the bell, the two make their way deeper into the school to an old computer lab next to the Spanish classroom. But where rows of monitors used to be, there is now a pull-up rig. Barbells, weights and kettlebells litter the corners, and rowers line the walls. The room smells like rubber.

They might still be in school, but once they walk through those doors, they’re also in Lancer CrossFit, a non-profit affiliate within Lawrence High School (LHS), named for its mascot.

The pair might be done with exams for the week, but they’ve got one more test to do: Open Workout 17.4.

“And I close my door, I blast my music, and the kids work out—3 … 2 … 1 … Go!” said Vincenzo DeLucia, the affiliate’s head coach and teacher. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

Air seemed scarce.

Brandy Digre stood over her barbell, hands on her knees.

She was more than 13 rounds and almost 20 minutes deep into the scaled version of Open Workout 17.3—a couplet of jumping pull-ups and increasingly heavy snatches, wherein the reward for completing the work before the time cap was more time to do even more work.

She shuffled her feet and gripped and ripped, catching the 95-lb. barbell a hair too far forward, dropping the weight and landing on her ass with half a smile on her face. Her coach, Stephen Hitt, stepped forward, twisting his arm to demonstrate external rotation. Someone called out the 90-second warning.

Another quick shuffle, another deep breath. This time her arms locked out overhead as she bounced neatly out of the catch to stand up. She grinned again, then logged one more snatch—plus 10 jumping pull-ups—before the clock hit 20 minutes and her workout was done.

An onlooker congratulated her on making it to the 95-lb. barbell.

“What was on my bar?” Digre asked, shocked. Ninety-five lb. was her snatch PR.

“The fact that I was lifting my PR weight and I did it four times made me feel pretty good,” she said.

Two years ago, Digre weighed 355 lb. at 5-foot-6 and could hardly move her own body weight, much less anything else. But today, a year and eight months after joining CrossFit Industrious in Lynnwood, Washington, the 36-year-old is 142 lb. lighter, three AbMats from a handstand push-up and halfway through her second CrossFit Games Open.

“It's just fun to be able to see what Dave Castro (will) throw at you and what you can do with it,” she said. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

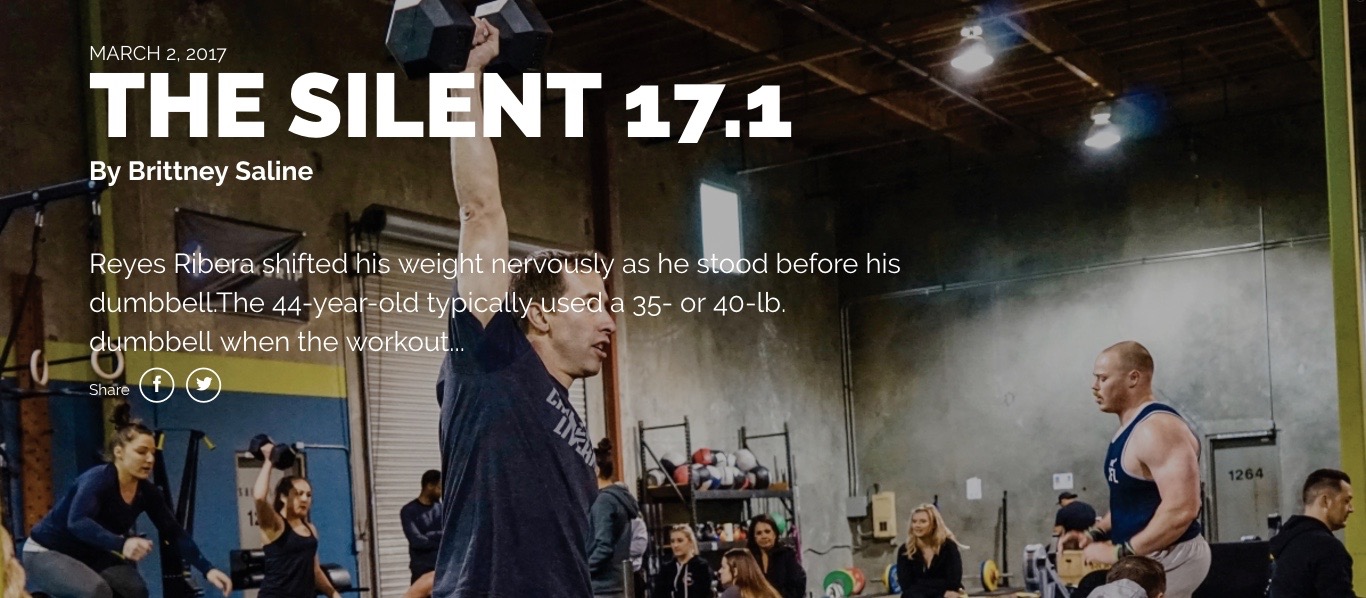

Reyes Ribera shifted his weight nervously as he stood before his dumbbell.

The 44-year-old typically used a 35- or 40-lb. dumbbell when the workout called for snatches, not the 50-lb. implement at his feet.

He glanced across the room, meeting the eyes of his coach and CrossFit Livermore owner, Matt Souza. Souza held up three fingers, indicating the final countdown, then slashed his fist through the air like a flagman of fitness. Ribera ripped his dumbbell off the ground.

As he worked, he focused on the rhythm of his breaths, trying to keep his heart rate steady. Step down, step up to the box, jump. With each leap, he felt the impact buzz through his feet. Ribera had no music to motivate him and heard neither scream nor cheer as he worked through the grueling couplet of dumbbell snatches and burpee box jump-overs.

Twenty minutes later, he’d completed 214 reps, just 11 reps short of finishing Open Workout 17.1.

Though Ribera, who is deaf, couldn’t hear his friends’ cheers, “you can almost feel the crowd’s energy, just like someone else would be able to hear it,” he said, speaking through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter. “They’re all there just wanting everybody to succeed as much as possible.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

Emily Celichowski eyed the rig above her. She’d already breezed through the first 10 55-lb. power snatches of Open Workout 16.3, and bar muscle-ups were up next.

Trouble was, she’d never done one before.

She jumped to the bar, extending her body in a tight arch before shoving herself back and up, attempting to launch herself over the bar. Miss. She tried again, kipping with even more force than before. Another miss, with a slight chicken wing.

Her coaches and fellow athletes screamed their encouragement from the sideline as the clock ticked down from 7 minutes.

On her third attempt, something clicked, and she found herself looking down from the top of the rig.

“Oh my God, I’m up here,” she thought.

She proceeded to knock out eight more bar muscle-ups before the time expired.

“(Each) one was like a huge victory.”

At the time, she was a CrossFit athlete of four years and a coach for nearly as long—yet last year was her first CrossFit Games Open. Despite encouraging her athletes to participate, for three years she avoided the worldwide test of fitness for fear of looking the fool. But when she finally decided to add her name to the hundreds of thousands of competitors across the world, she was rewarded with a brand-new skill and a freshly conquered fear.

“I was definitely glad that I did it,” she said. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

For the first time in history, an Open workout began with muscle-ups.

Victor Stanley grinned before Open Workout 15.3. A CrossFit athlete of seven years, he had experience on his side and was confident he could easily kip through the 7 reps at the start of each round.

The same could not be said for Stanley’s workout partner. Though the 20-something athlete was almost a decade younger than Stanley—who was 34 at the time—he had just learned the muscle-up and lacked finesse and efficiency.

“I was happy about that one because I finally got him on one,” Stanley said after beating his younger buddy by several rounds. “The next year he had muscle-ups down and there was no catching him after that.”

This year, Stanley, now 36, will be chasing kids his own age in the 2017 Reebok CrossFit Games Open as he competes in the inaugural Masters 35-39 Division.

“I am extremely excited about the opportunity it presents,” he said. “I feel this makes the competitive aspect a little more fun because I actually feel like I am in the hunt now.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

Time-tested truth: Proximity to the CrossFit Games Open directly influences how often your coach programs thrusters and burpees.

In the weeks before the first live announcement, affiliates across the world ramp up their skill work, resurrect past Open workouts and concoct new ones built of rep schemes and loads seen in Opens past.

But what do they do when the Open arrives and they’ve still got to program for the other days of the week surrounding the Open workout? And how do they continue to increase fitness while also leaving room to accommodate its most comprehensive test? CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

It’s the final event, and just a few points separate teams.

The DJ’s laying down beats, and the crowd is on its feet, screaming equally loudly for a team dressed in “Walking Dead” zombie makeup and a team of Regionals hopefuls.

It’s not the CrossFit Games, but the CrossFit Games Open is packed with plenty of spirit at affiliates around the world.

“It's a big huge party for five weeks,” said Mike Wuest, owner of CrossFit COMO in Columbia, Missouri.

An affiliate owner since 2013, Wuest has hosted the Open for his athletes since 2014. For the past two years, he’s done it with a twist, turning the Open into an in-house intramural competition. Though athletes still register for the Open on the CrossFit Games site and put up a score recorded by a judge, the primary purpose of the intramural Open is to create unity and have fun.

“One thing we really focused on was, ‘Let’s not worry about people being the best athlete,'" Wuest said. "We really focus on 'What kind of experience could that team or that group bring to the gym every Friday night?’” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

“No rep!”

In less than a month, CrossFit athletes everywhere will echo the two most famous words of CrossFit Games judge Adrian “Boz” Bozman.

We test our fitness in the gym every day, but once a year we keep score on a worldwide whiteboard. The best advance to Regionals and eventually the CrossFit Games, but for most of us, the Open is our Games: a chance to measure our growth, see where we stack up and note what needs improvement.

But how do affiliate owners turn accountants and nurses into Bozmanites fit to scrutinize the squat?

It’s not that athletes don’t try hard in regular classes—CrossFit is not known for attracting people who give less than 100 percent—but rather that having every rep judged can alert athletes to issues they didn’t know were there. For example, Update Show host Pat Sherwood needed a check-up himself back in 2013.

“I think sometimes people don't know necessarily that they are cheating range of motion,” said Erica Folk, owner of CrossFit Warrior RX in Crystal City, Missouri. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

MIND GAMES

“Make it a great day—or not; the choice is yours.”

For four years, that adage was drilled into my head, the daily sign-off after my high school’s morning announcements. I always rolled my eyes. Sure, whatever, I thought. As if I could control how my day was going to go.

Cut to 10 years later, when Julie Foucher tore her Achilles on a box jump-over at the 2015 Central Regional, ending her final season at regionals rather than the Games. Not more than an hour after the season-ending injury, Foucher joked about wearing a boot at her upcoming wedding and said, “I have a lot of things to look forward to.”

She made it a great day, taking to the floor in an over-sized black boot in that afternoon’s 250-foot handstand walk event and outpacing many of her peers across the floor despite having to walk to the starting mat while others ran. She smiled and waved to the crowd, while those watching were brought to tears.

I asked myself, “How the hell did she do it?”

To find out, I got Foucher on the phone, along with a man who has finished no more than three spots outside the CrossFit Games podium for the last four years, Scott Panchik, and a woman who has twice been the favorite to win the CrossFit Games and twice been held back by injuries, Kara Webb.

If anyone could teach me the mysteries of mental strength, it would be them. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

school of fitness

Like many top CrossFit Games athletes, Nicholas Paladino, Angelo DiCicco and Vincent Ramirez begin their days with a workout—the first of several daily training sessions that total six to eight hours of work.

But unlike podium finishers a few years their senior—Paladino and DiCicco won the 16-17 and 14-15 Teenage Boys Divisions of the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games; Ramirez took third in the 14-15 Division—these fitness fiends punctuate their days not with coaching or administrative work, but with English and economics.

More than 7,550 teenagers competed in the 2016 Reebok CrossFit Games Open alone, and as CrossFit athletes get younger and fitter—at 16, DiCicco matches CrossFit Games veteran Chris Spealler’s snatch PR of 235 lb.—some of CrossFit’s top teens are forgoing traditional high school education in favor of more flexible options like homeschooling and online classes.

“I've never really looked back,” said 17-year-old Paladino, who graduated in February from Penn Foster Online High School after completing two years’ worth of coursework in just six months. “This has turned out really well for me; I'm pretty happy with my decision.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

FINDING THEMSELVES THROUGH FITNESS

Haley Adams walked through the congested hallways of her high school, clutching her textbooks as students streamed around her. She heard a low snicker to the side, and braced herself. A group of male students shot a string of questions her way.

“Do you even lift?”

“Are you going to the CrossFit Games?”

“They don’t mean it in a nice way, either,” Adams said.

One boy grabbed Adams’ bicep in mock awe.

“Girls aren’t supposed to have muscles,” he said.

Adams shrugged him off. The constant taunts about her chiseled arms and devotion to training at College Hill CrossFit in Greensboro, North Carolina, used to bother her. But not since she won the Teenage Girls 14-15 division of the 2016 Reebok CrossFit Games Open. After 10 months of CrossFit, she earned her spot in Carson, California, with two first-place finishes, never placing outside the top seven worldwide.

“Now that I’ve actually got that spot, (the insults) don’t matter anymore,” she said. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

TIA-CLAIR TOOMEY'S SECOND CHANCE

Tia-Clair Toomey never expected to podium at the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games. Hell, she never expected to be there in 2015 in the first place.

“Next year was my goal,” the 22-year-old said.

But after taking third at the 2015 Pacific Regional—her second regional appearance—she reached her goal a year early, and by the start of the final Games event, Pedal to the Metal, just 21 points separated Toomey, in fourth, from fellow Aussie Kara Webb, in third. Even then, her sights weren’t set on a medal.

“All my focus was simply just to stay at that position,” she said. “I honestly never went into the Games thinking I was going to win.”

Imagine her surprise a few moments later in the tunnel when a Reebok staffer gave her the good news: she had risen to the second podium spot.

“I can't believe I was able to pull out second,” she said. “I'm still struck by it.”

Less than five months later, after Toomey helped the Pacific Team to a third-place finish at the 2015 CrossFit Invitational in Madrid, she lifted her way into the top qualifying spot for the 2016 Australian Olympic Team, snatching 83 kilos (182.9 lb.) and clean and jerking 111 kilos (244.7 lb.) with a 58-kg bodyweight (127.8 lb.) at the Australian Open in December. This July, she hopes to compete at both the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro and the 2016 Reebok CrossFit Games.

“I always wanted to go to the Olympics; it would be such an honor,” she said. “And to make the CrossFit Games (also) would be unreal...I would do anything to just be there for both of them.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

DUCT TAPE AND DETERMINATION

Last Friday night, thousands of CrossFit athletes across the globe gathered to compete in Open Workout 16.4. They loaded their barbells and adjusted their footstraps before facing the wall, arms up like crooks, to get measured for handstand push-ups.

Kelsey Whirley, a 20-year-old athlete from Hoosier CrossFit in Bloomington, Indiana, had a bit more to do. Perched upside down against the gym wall, her judge drew white boxes in chalk around each of Whirley’s hands. After, she wrapped her medicine ball in neon orange duct tape.

It wasn’t just for show. At 15, Whirley was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), an incurable genetic disorder that causes retinal cell death, resulting in vision loss and eventual blindness. The markings on the floor showed Whirley where to put her hands, and tricking out the black and red medicine ball helped it stand out from the red target above.

The diagnosis ended an almost lifelong ambition to play professional basketball. But in CrossFit, Whirley said, she’s found new purpose and a potential career path.

“I had a huge hole in my heart from losing my dream of playing basketball,” she said. “I didn't think I would ever get over it, but CrossFit overflowed that empty space.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

fitness in the raw

It was overcast and about 50 degrees Fahrenheit—perfect burpee weather. Barni Böjte stepped outside and cranked his iPod to Stellar Revival, full blast. He introduced himself to the camera and dropped a thick Rogue bumper onto a clunky metal machine that looked more typewriter than scale.

“Exactly 20 kilos,” he said with satisfaction, adjusting the counterweight. A few moments later, his father called, “Három, kettő, egy megy”—“three, two one, go” in Hungarian—and Böjte lunged his way through the dirt and around discarded corn cobs holding 95 lb. overhead as he completed the first few reps of Open Workout 16.1.

“My first plan was to do one round every two minutes, and if I couldn’t hold that, really just don't die,” the 18-year-old said.

Clad in a Lacee Kovacs jersey replica, Böjte lunged the 25-foot course dividing piles of scrap wood and metal, capping each lap with eight burpees and eight chest-to-bar pull-ups. The dusty, uneven grass was marked with a white spray-painted line every five feet, and with each butterfly pull-up, the wooden masts of a homemade pull-up rig threatened to tear themselves from the side of the shed to which they were mounted.

When the time expired 20 minutes later, Böjte collapsed to the ground, 247 reps in the bank, wheezing as he shoved away the kisses of his small black dog, Malac (Hungarian for “pig”).

“The first 10 minutes were OK, but at the end, I almost died,” he said.

Böjte lives with his parents and baby sister in Sàrpatak, a small town cradled between the Transylvanian Alps and the Eastern Carpathians in the center of Romania. Though he lives almost 100 miles from the nearest CrossFit affiliate, that hasn’t stopped him from doing CrossFit—or competing in the 2016 Reebok CrossFit Games Open. After discovering CrossFit online about two years ago, the teenager built a gym out of concrete and wood, and with a little determination, he plans on qualifying for the Meridian Regional one day.

“Next year,” he said, laughing. “Next year.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

AND FITNESS FOR LIFE

Last January, Daniel Casey became a CrossFit sensation. At a bodyweight of around 400 lb.—down from around 550 lb. after a year of CrossFit—he competed in the inaugural scaled option of the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games Open, completing each of the five workouts for a 5,202nd-place finish in the Central East Region. His story inspired thousands across social media, many of whom contacted Casey and credited him with motivating them to join their local CrossFit affiliates.

It took courage for Casey to share his story. It felt like his first day of CrossFit all over again.

“When I first started, I was afraid to walk into the gym, thinking, ‘People are gonna look at me, people are gonna laugh at me …’ and that was just a gym in a relatively small city in a country area of Tennessee,” he recalled. “What happens when a picture of my 400-lb. butt doing a snatch, with my fricken stomach hanging out, goes worldwide?”

Before his story came out, he had a heart-to-heart with one of his coaches, Brett DeBruin, who lost 145 lb. doing CrossFit before becoming a coach at CrossFit East 10 in Johnson City, Tennessee.

Casey recalled DeBruin saying, "'You realize I’ve got people that come in here and they see my before and after picture and they’re like “Wow, if he can do it, I can do it … But that’s just a few people; you have the ability to send this whole thing worldwide … and you can't be worried about the people that are gonna hate on it."' And the massive outpouring of support just made it all worthwhile.”

The Open came and went, and CrossFit athletes went back to their daily lives. Casey went back to his, too. And while the Open is a time to celebrate our accomplishments, life is as much valleys as peaks, and Casey’s toughest tests were yet to come. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

AND FITNESS FOR ALL

Just more than a year ago, Daniel Casey couldn’t find a scale that could weigh him.

Knowing he weighed more than 300 lb., the limit for most conventional scales, he tried the scale at the local fitness center in Johnson City, Tennessee. It bottomed out at 400 lb.

Local obesity clinics only had scales measuring up to 450 lb., so he went to Walmart. The manager led him through a set of double doors to the store’s warehouse shipping scale. Expecting to see a number around 500 lb., Casey blanched when the screen read 550 lb., flashed “error” and went dark.

“I walked in to CrossFit the next day and I went harder than I had ever done,” Casey recalled.

That day was in October of 2013. Casey joined CrossFit East 10 a few weeks prior, and his first workout—3 rounds of step-ups, wall push-ups and air squats to a bench—“completely destroyed” him, he said.

Today, 13 months later and around 150 lb. lighter, the 23-year-old is preparing to compete in the inaugural-scaled option of the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games Open.

“I can call myself an athlete now,” he said. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

From Pirouettes to Pistols

Brooke Ence left behind a lifetime of dance to discover a new passion in CrossFit.

It was the ninth event of the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games, and Brooke Ence couldn't see. Competitors to each side sported sunglasses to block the California sun's piercing gaze; Ence, a rookie, had none.

Athletes had two 20-second windows to establish a max clean-and-jerk. In her first window, Ence put 227 pounds on the board. Feeling lightheaded as she locked out the weight, she was tempted to go for a more modest 235 pounds on her second attempt instead of the 242 pounds her coach, Michael Caza-youx, had prescribed. After all, she’d hit her lifetime PR of 245 pounds just two weeks prior, and that was without two days of CrossFit Games events beforehand.

She shook off her doubt. “I thought, Nope, he gave me that number for a reason,” Ence recounts. She loaded her bar with 242 pounds and asked to borrow her judge’s sunglasses. After a slight bounce to wind up her hamstrings, she pulled the weight and dropped in a squat, popping the barbell to regrip after she rose. Four seconds and one deep breath later, she dipped, drove and locked out the weight. Breaking into a grin before she’d even finished the lift, she slammed the bar to the ground and tore off her weight belt in celebration.

At 2 pounds more than four-time Games competitor Lindsey Valenzuela would lift, Ence’s score was good enough for first place. She went on to earn 14th overall in her debut Games appearance with two event wins and four top-10 finishes.

“I’ve literally watched that video so many times because the clean is so sexy,” the 27-year-old says, laughing. “It was just gratifying, and it proves that I was at the Games because I was supposed to be there and I earned it. I’m just as good as anybody else.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

ONE HELL OF A COMEBACK

All three women on CrossFit Jääkarhu's team have faced afflictions that threatened to end their competitive careers, from heart and hip surgery to cancer, and nonetheless emerged not only unscathed but fit enough to qualify for the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games.

While Ingrid Kantola's heart surgery happened years ago, Karen Pierce and Jessica Estrada returned to CrossFit training after chemotherapy and hip surgery, only a few months before the 2015 South Regional.

"It has been a roller coaster, to say the least," Michael Winchester, the team coach and co-owner of the 8-month-old affiliate. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

THE WEIGHTLIFTER'S MINDSET

It was Saturday evening at the 2015 Reebok CrossFit Games as Lucas Parker prepared to take the platform for Clean and Jerk, and he had to pee.

“Dang, I just went to the bathroom like 30 seconds ago, why do I have to pee again?” he asked himself.

Though it was his fifth Games appearance and he was no weightlifting rookie—his 2013 British Columbia Provincial Championships snatch record of 132 kilos (290 lb.) still stands today—he felt jittery, his heart throbbing in his throat. He reminded himself this was a good thing.

“These are just the things that happen when you’re a caveman running away from a sabertooth tiger,” he said. “The fight or flight system is kicking in, and this is what I want.”

He took a deep breath and shook out his legs, adjusting his privates to get “loose and comfortable” as the countdown boomed throughout the tennis stadium:

Three, two, one, lift. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

DEADLIFTS OVER DEATH

It was June 19, 2013. The Tennessean air smelled of summer, and Jeff Goebel went to the lake. Along the way, he stopped for a fifth of Jack Daniels.

He’d just buried his deceased father’s best friend, Tim, a beloved mentor for the three decades since his father passed. Tim lost his battle with cancer two days before Father’s Day that year.

Goebel paid for the liquor and drove to the shore.

Driving, he replayed the bitter words exchanged with his daughter, just feet away from the freshly upturned dirt where he left Tim to rest. She no longer loved him, he thought, and that made two children lost.

Two days earlier marked what would have been the 17th birthday of Goebel’s son, Jake. A failed attempt to induce a high via partial self-asphyxiation ended Jake’s young life two and a half years prior.

Goebel parked his car and sailed his boat across the lake. After dropping the anchor, he unpacked the pills, pain medication to treat the spondylolisthesis in his back, remnant of an old military injury. Goebel hadn’t needed them since starting CrossFit in 2012, but still he filled the prescriptions, just in case.

He swallowed them all, chasing the pills with all 750 milliliters of the acrid spirits.

“The last thing I remember saying out loud was, ‘Take me home, I want to be with Jake,’” Goebel recalled. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

FAITH IN FITNESS

Dave Castro announced, seconds before the men took the floor for the last time at the 2014 Reebok CrossFit Games. “You will do 60 reps for time.” Dan Bailey smothered a grin. The first time he performed Grace (30 clean-and-jerks for time), he finished in 1:34. For Bailey, Double Grace was a welcome finish to a gnarly weekend. “I was pumped,” he told CrossFit Media after he won his heat to take third in the event. He caught the 135-pound barbell with shallow power cleans, driving without pause into snappy push jerks. He repped them out into metronomic singles, finishing in 5:09, the fastest time yet.

In the final heat, Jason Khalipa beat Bailey’s time by 1.2 seconds. Rich Froning won the event in 5:05.6. “He’s tough to catch,” Bailey says now of the four-time CrossFit Games champion. Which is not to say that Bailey hasn’t been trying. In fact, he has been chasing the four-time Fittest Man on Earth since 2011, when Bailey took sixth at the Games. Since then, Bailey has bested Froning in nine Games events, but the podium has remained stubbornly just beyond reach, with Bailey scoring sixth-, eighth- and 10th-place finishes in 2012, 2013 and 2014. Froning’s retirement from individual competition following the 2014 Games means Bailey will never have the chance to share the podium with the champ. “But I never let that discourage me too much,” Bailey says. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

MORE THAN A GAMES ATHLETE

The air was cold as four-time CrossFit Games athlete Michelle Kinney and her girlfriend, Emily Schromm, stepped into a swaying gondola at Keystone Ski Resort in Colorado, snowboards tucked under their arms. It was late on a Sunday morning, yet the crowds were thin, and the dusty slopes in the distance promised a good powder day.

Two days earlier, Kinney hosted Open Workout 15.3 at her new affiliate, CrossFit Park Hill in Denver, where she moved to be closer to her girlfriend of a year. Sidelined from the 2015 season due to several injuries, ranging from torn labrums in her right hip and left shoulder to a partial tear in her left rotator cuff, Kinney clutched a judge’s clipboard as the clock counted down.

“I got chills as if I was about to do it, and then I had a reality check,” she said. “It’s definitely a tough pill to swallow.”

When the 14-minute AMRAP of muscle-ups, wall-ball shots and double-unders was over, Kinney signed off on Schromm’s 318 reps. Now, as the steel cable tugged the pair toward the white peaks of the Rockies, Kinney sipped coffee from a paper cup as she remembered the joy of cheering for her girlfriend.

“All my sadness from not competing goes away when I watch her,” she said. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

ELEVEN YEARS AFTER MOSUL

Maj. Scott Smiley had been in Iraq for only six months before he lost his vision.

Back then he was a first lieutenant with Alpha Company of the U.S. Army and led a 45-man, 4-Stryker vehicle platoon in Mosul, Iraq. Assigned to help secure and rebuild the city after the U.S.-led invasion, most of his time was spent training Iraqi police, and helping civilians by providing food, electricity and gasoline.

But on April 6, 2004, his unit was ordered to locate a vehicle loaded with explosives in the two-million-person city. The afternoon sun beat its 90-degree heat onto the Stryker that day as he wove through the dusty, unkept streets.

Near a small marketplace, he noticed a silver Opel sedan with its rear bumper strangely low to the ground.

“That could mean two things,” he explained. “It could be that the shocks and suspension are out or that there’s something heavy in there.”

With his Stryker parked 30 yards away from the sedan, Smiley went to the turret and told the driver to exit the vehicle. He watched as the driver raised his hands from the steering wheel and glanced over his shoulder before shaking his head.

Smiley repeated the command and watched as the driver shook his head once again before releasing the brake on the sedan and pulling forward. In response, Smiley fired two warning shots into the ground with his M4 rifle before it all went black.

The driver had set off the bomb, disintegrating the sedan and sending pieces of shrapnel through both of Smiley’s eyes, blinding him. One piece lodged in the left frontal lobe of his brain, and the other cut through his optic nerve. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

DANCING WITH (DIS)ABILITY

Sam Dancer held his breath as he watched his athlete, James, wrap his thumbs around the 45-pound barbell, settling into a partial squat. The heaviest thing James had ever held above his head was a PVC pipe, and the snatch is no novice’s movement.

Looking straight ahead, James inhaled and pulled. The weight floated upward; he caught it overhead and sank into a deep squat. After he dropped the bar, he gave Dancer a bone-shattering high-five.

“He did an Oly lift, and it blew me away,” Dancer said. “I can’t teach some 20-year-olds who have been playing sports their entire lives to snatch like that.”

James, 27, is a CrossFit athlete of about four months. He loves to deadlift, bench-press and jump rope, and he also has Down syndrome. Once a week, he trains with Dancer — who took 10th at the Central Regional this year — at QTown CrossFit, Dancer’s affiliate in Quincy, Illinois.

“I like CrossFit because I’m good,” James said. “I also have lots of friends here. But mostly because I’m good.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

MEMORIAL DAY MURPH AT 41 WEEKS

Steely gray clouds hung over CrossFit Praus, an affiliate nestled between a truck maintenance center and plumbing service shop in a dusty industrial lot on the outskirts of Fort Wayne, Indiana. It was Memorial Day, and Nicole Schwanz, 28, was on her final 800 meters of a half-“Murph.”

She had survived the first 800 meters, followed by 50 pull-ups, 100 push-ups and 150 air squats. Now, as she strode along the sidewalk for the final leg, she felt a cramp in her abdomen. But Schwanz, a CrossFit athlete of two years, knew how to push through discomfort.

Shrugging off the dull ache, she finished at around the 42-minute mark. Less than two hours later, she gave birth to a healthy baby boy. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

SURVIVING THE IED

Army Combat Engineer Nick Koulchar was hit by an improvised explosive device when insurgents seized Sadir City in Iraq on Aug. 26, 2008.

He survived.

On the night of the explosion, Koulchar was providing cover from the roof of his truck while comrades scouted for bombs. Suddenly, everything went dark as a cloud of dust erupted around him.

He crashed to the center of the truck, legs collapsing beneath him.

“I’m thinking, ‘Damn, my legs are broke. Why does dumb stuff always happen to me?’” Koulchar said.

He urged his commander to tend to the driver, seriously injured and trapped behind the truck door, which was welded shut from the explosion’s heat. But as medics struggled to secure tourniquets to his bleeding legs, he realized just how bad it was.

“I remember the air was really cool, and I was staring at the stars and thinking to myself that I wasn’t gonna die,” he said. “I kept telling myself that my brother was not gonna bury me.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

THE WOMEN OF THE LIVESTREAM

At the 2014 Southern California Regional, cameras panned to Josh Bridges in Event 4. CrossFit fans all over the world watched as his chest hit the ground for his last 3 burpees before he screamed in triumph, taking the event record in 8:18.

But Bridges wasn’t the only one working that day. While he pumped out strict handstand push-ups, front squats and burpees, Kathy Elder stood in a production truck nearby, sipping her coffee as she called out commands.

The four women on her team carried out her every request.

“We are the live stream team,” Elder explained. “What that means is when people sit down with their computers at home to watch the live stream … our team is making that whole thing happen.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

PUNCH, SHOOT AND SNATCH

Frank Trigg’s heart hammered as he fled, sprinting as fast as his heavy boots and fatigues would allow. Bullets pelted the air to his side. He pulled his hat low to meet his sunglasses and returned fire, twisting sideways to aim his rifle at the cops to his left as he tore across the strip-mall lot.

He felt the shot before he heard it. His chest folded in as he flew backward into an 8-foot plate-glass window, landing lifelessly on a bed of glass shards in a small trinket shop. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

GREG PANORA

Greg Panora had it made.

An American record-holding powerlifter in the 242-pound weight class, he was living the life most lifters only dream of, training at Westside Barbell with legendary powerlifting coach Louie Simmons. But after suffering a major stroke at age 29, he felt lost — until he found CrossFit.

Panora started lifting weights to get better at sports. Throughout high school, he dabbled in shot put, wrestling, football and basketball, trying to find his place. But when he bench-pressed 405 pounds at age 16, he realized he’d already found it.

“I was better at lifting weights than any of the sports I was playing,” Panora said.

During his senior year in the small town of Stow, Massachusetts, Panora was recruited to play college football. But he had a dream to become a professional powerlifter. His dad told him to go to college instead.

So he went to the University of Maine, studying to become a high school history teacher. Though he continued to lift, breaking the junior world record at age 21 with a 940-pound squat, a 600-pound bench press and a 800-pound deadlift, four years in the classroom brought him down from the clouds. He resolved to join the ranks of the 9-to-5 working class.

Even after Simmons himself asked Panora when he planned to move to Columbus, Ohio, to train at Westside, Panora was unyielding.

“I’m ready for the next phase in my life,” he said.

“Well, if you want to be the best in the world, come see me,” Simmons said to Panora. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

FITTER AT 51: JERRY WILSON

Moments before the Leaderboard closed after the inaugural Masters Qualifier, Jerry Wilson poured himself a glass of scotch.

Though his wife and two adult children sat around the dinner table hitting “refresh” on their smartphones, Wilson couldn’t bring himself to look at the Leaderboard. He made that mistake last year, celebrating prematurely before watching his name fall to 21st place in the Masters Men 50-54 Division after the 2013 Open, just one place short of qualification for the 2013 Reebok CrossFit Games.

“I ran out of the house, yelling, ‘Honey, I think I’m gonna make it!’” Wilson recounted. “Then it jumped to 21st and I just sat at the computer and put my hands on my head. Refreshing didn’t help after that.”

But this time, his name stayed put when the minute turned over. Finishing in eighth place in his division, the CrossFit athlete of seven years is headed to Carson, California, for his CrossFit Games debut.

His drink lay forgotten on the table, ice melting in the glass.

“I was so excited,” he said. “I was running around like a little kid.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

COMPETING IN 270 SQUARE FEET

Though the temperature was only 30 degrees in West Lafayette, Ind., Erika Ugianskis cracked the window in her garage late Sunday morning. About to take on the brutish chipper of the fourth Open workout, she knew she’d be sweating soon enough.

She placed her iPod on its stand, flicking to her favorite Pandora station—a mix of Armin van Buuren, Deadmau5 and Swedish House Mafia.

There was no caution tape to hold back a throbbing crowd; indeed, there was no crowd at all as she pushed off for her first pull on the erg. A garage CrossFitter of six years, Ugianskis is used being her own cheerleader.

“I’m a very self-motivated individual,” she said. “I am my own fiercest competitor.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

FITTEST AT 15

She moved like a machine.

Wall-ball shots, power snatches, box-jump-overs, pull-ups … the movement didn’t matter. Each rep looked identical to the previous, and she only got faster as her rep count climbed. Her face a model of composure, she embraced victory after victory with quiet humility.

No, her name is not Julie Foucher. It’s Sydney Sullivan, and in the inaugural teen competition at the CrossFit Games, she won six out of seven events to take the gold in the Teen girls 14-15 division. She sealed the victory even before the competition ended, entering the final event with a 70-point lead over Megan Trupp, who placed second.

“It’s awesome; it’s really exciting,” Sydney, 15, said. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

ALL IN: JOHN FORTUNE

While most of the small city of Geneva, Ohio slept, John Fortune pulled the last few strokes of a 10,000-m row. Moonlight streamed in from the bay doors of A-County CrossFit and glanced off the clock. It was just after 1 a.m.

Working 60 hours per week as a firefighter and paramedic, running an affiliate and training for the 2014 Central East Regional, Fortune can’t afford to waste time on luxuries like sleep.

“My friends call me ‘Petri Dish,’” Fortune said. “They say I was genetically engineered because I don’t sleep and I’m so energetic.”

He kicked out of the straps and called it a night. Thankfully, his commute was short—the CrossFit athlete of just more than a year sleeps in a 12-by-12-foot, bare concrete room tucked behind his affiliate’s storage closet.

“I live in my box,” he said. “I put all my life savings in here, so when I say CrossFit is my life, literally, it’s my life.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

#NOOGASTRONG

On July 16, 2015, 24-year-old Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez opened fire at two military centers in Chattanooga, Tennessee, killing four U.S. Marines and one U.S. Navy sailor. Though Abdulazeez’s father had previously been investigated by the FBI and put on the terrorism watch list, he was later removed, and Abdulazeez, a former high school wrestler and promising electrical engineer, had an unblemished record.

The attacks shook the Hixson community, a quiet suburb in a town of less than 200,000 people.

“It’s the kind of place you can go next door and borrow eggs from your neighbor,” said Eric Griffith, a 41-year-old Chattanooga resident. “I can’t go to the grocery store without seeing six people I know.”

Griffith had been kayaking on the Tellico River the day of the attacks, darting across rolling rapids fed by a week’s worth of rain. Pausing in a quiet eddy, he flicked on talk radio to the tune of tragedy.

“It threw me instantly back to 9/11, me being at work and hearing the same radio chatter, not knowing what’s going on,” he said. “I just remember being in shock.”

On the drive home, his phone chirped with the sound of a new text message.

“What are we going to do?” it read. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

RUNNING THE BOSTON MARATHON

It was a Monday when nearly 23,000 runners gathered for this year’s Boston Marathon. Just under five hours into the event, shouts of mid-race jubilation turned to cries of terror as explosions ransacked the finish line area. The blasts killed three people and injured over 170 others.

Jennifer Murray, owner of CrossFit Justice in Milford, Mich., was half-a-block away from the site of the first explosion. CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

JUSTIN BIEBER ('S SOUND GUY) TAKES ON THE OPEN

It’s been nine months since Arnie Hernandez has seen the inside of his home box, CrossFit VTG. Days off don’t come easy when you’re the head sound guy for Justin Bieber’s world tour.

Each week, the 41-year-old roadie completes the Open Workout in a different box

“Some will have nice equipment, some are more stripped down, but the vibe in each is the same,” he says. “A common thread is the hospitality that they’ve all shown to me as a foreigner.”

Although he lives on a bus, he never misses a workout, carrying a barbell and plates with him on the road. On days off, he drops in at a local affiliate. On show night, he works out while the band warms up.

“When the opening acts are setting up, I’ll pull out my barbell,” he says. “While they’re doing the sound check, I’m at the front of house, squatting.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

RECOLETA GOES BIG, FAST

A peculiar sight stood out among the stray dogs and unmarked vans surrounding the grounds of the Chimkowe Event Center: a bright green double-decker filled most of the Peñalolén street.

The bus’s exterior read BIGG on the Road to Regionals, and inside were 70 members of BIGG CrossFit Recoleta holding drums and flags in their laps as they finished their 26-hour journey from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to support their regional team BIGG Friends.

“Every achievement we make is important, but the most important thing is to prove we’re a big family,” said affiliate owner Ignacio Alsogaray.

Dancing and singing in the stands, the family celebrated all weekend long as though the three-day regional competition was the CrossFit Games.

“We came to Chile to be in the top three … but we never thought we were gonna make it (to the Games),” Alsogaray said.

But the 9-month-old affiliate exceeded its own expectations. When the weekend ended, their team stood at the top of the podium as Latin America’s sole representative at the 2014 Reebok CrossFit Games.

BIGG Friends placed in the top five in the majority of the events, including three first-place finishes. But two low finishes nearly let another team pass them in the overall standings. On the final day of the regional, BIGG Friends and CrossFit SP Hulks had to fight for the top spot, and BIGG Friends came out ahead by just 1 point.

“When (the results) were official … it was like pure joy,” said team captain Titus Thut. “It’s like a dream coming true.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

FIT TO TEACH

At 16 years old, Meredith Davis (then Wittman) was strong.

A ballerina of 12 years, her thick, sinewy thighs propelled her nimbly across the floor as music swelled overhead. Her back muscles rippling as she extended in a graceful arch, she looked to her instructors for approval.

“‘Your legs look like tree trunks,’” Davis quoted her teacher. “‘You should stretch them out a bit, because we don’t want to look like that.’”

The callous remark was the prelude to a 10-year battle with distorted body image and eating disorders. But when CrossFit taught Davis to love PRs more than pants size, she ended the war and took up a cause. The dancer-turned-science-teacher would use CrossFit to forge an army of fit educators—the role models she never had.

“It’s important as an educator to set a positive example,” she said. “Your body is meant to do things. It’s not just meant to hold clothing or to look a certain way.”

REIGN ENDER

Orlando Trejo was the Rich Froning of Latin America.

The region’s Open and regional victor for two years, it seemed Trejo’s reign might last forever. But when he took second to Leonidas Jenkins in the Open this year, fans wondered: Could Trejo be defeated?

Conor Murphy and Joel Bran, last year’s second- and third-place regional finishers, were the favorites to take Trejo’s place. Newcomer Mark Desin also looked to make an impression after taking third in the Open this year.

But when the Leaderboard shifted for the last time in Santiago, Chile, a new name held the top spot: Emmanuel Maldonado, of CrossFit SJU in Puerto Rico.

He took the podium quietly, earning the sole qualifying spot without winning a single event. Finishing in the top 10 in all but one event, he proved his fitness with consistency.

As Maldonado looked into the stands from his perch atop the podium, he was just as surprised by his victory as the crowd was.

“I was expecting to be in the top 10, but it was more than a shock to win,” the 24-year-old said. “It was an awesome feeling.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY

THE MAN WHO CHALLENGED FRONING

“In every workout, I’m looking to beat him,” Scott Panchik said of three-time CrossFit Games champion Rich Froning.

Before Nasty Girls V2 at the 2014 Central East Regional, commentator Bill Grundler guessed the race would come down to the pistols. But in the end, it came down to an un-prescribed push press.

Through the three rounds, Froning and Panchik were never more than a few reps apart. Froning was faster on the pistols, but Panchik made up for it on the hang power cleans. In the final round, the men met on the mat for the last 10 hang power cleans. Panchik caught up with Froning and they finished their final rep in unison.

While Panchik tossed the barbell to the ground, and paused before jumping over the bouncing bar, Froning popped the barbell over his head to step onto the finish mat a fraction of a second before Panchik.

“That’s why he’s the champ,” Panchik said with a laugh. “Only Rich would think to throw it over his head.”

Froning won the regional, as expected, but he seemed to have a true challenger. Panchik forced Froning to go faster than he wanted, and repeatedly forced the judges to pick a winner based on fractions of a second.

“It’s always a good feeling to look over and see him next to you,” Panchik said. “It tells you that you’re doing something right.” CONTINUE TO FULL STORY